Fixin and the Vineyards of Domaine Berthaut-Gerbet

By PW – April 2018

We are greatly indebted to geologist Brenna Quigley for her illustrations and for putting the physical and geologic aspects of these vineyards into words far more meaningful than we could have written on our own. (And also for lending us her hammer so we could smash rocks just like she does.) www.brennaquigley.com

We are also greatly indebted to geologists Françoise Vannier and Emmanuel Chevigny of Adama Terroirs Viticoles who created the soil and bedrock maps for Fixin that Brenna based part her work on. www.adama-terroirs.fr

A Fixin Primer

Fixin’s reputation for rusticity

In 1855, Dr. Lavalle wrote that Fixin Clos de la Perrière had long been placed among the Têtes de Cuvées (best wines) of Burgundy, and that its owner, the Marquis de Montmort, sold it for the same price as his Chambertin. Lavalle also compared the quality of Fixin Les Arvelets to Gevrey [Clos] Saint-Jacques.

Yet, today, Fixin is a relatively ignored appellation with a reputation for producing rustic wines. What happened?

In Making Sense of Burgundy, Matt Kramer writes that “One of the reasons that the Fixin light remains so well hidden under a bushel is that the appellation of Fixin is also entitled to sell its wines under the lesser name of Côte de Nuits-Villages.”

For several decades there was such a demand in Europe for the affordable regional appellations Côte de Beaune-Villages and Côte de Nuits-Villages that it exceeded the output of their dedicated areas of production. So négociants turned to the communes that could sell their wines either under their village appellations or under the lesser ‘Côte de’ regional appellations. Of course, regional-level prices were offered —and accepted— not village-level prices.

What happened to Fixin in the Côte de Nuits happened also in the Côte de Beaune to Santenay and Saint-Aubin, for example. Olivier Lamy tells us about the latter:

To experience something different, most French students at schools of viticulture and enology travel to other countries for their internships. For his, Olivier chose to go to Méo-Camuzet in the Côte de Nuits: “I didn’t travel far, but I got to witness a culture of Pinot Noir that was very different from ours in Saint-Aubin. Méo’s vineyards were extremely well cultivated. They had great old massal selections with small bunches. They did things we didn’t do here: they removed all the lateral shoots by hand; even with yields of 20 hl/ha in 1995, they did a green harvest; they sorted stringently at harvest; the cellar work was spot on; they bottled by hand… I had a notebook where I wrote down what they did in the cellar. In the evenings, I applied the same methods on our wines in Saint-Aubin. It didn’t always work: we didn’t have the same vineyards.”

With the poor economic incentive of regional-level pricing, it was not feasible for growers in appellations such as Santenay, Saint-Aubin, and Fixin to manage their vineyards with an eye towards producing grapes of the same quality as the ones grown in prestigious appellations. Nor was it possible for them to invest in cutting-edge equipment in the winery. Though generalizations are always insulting, as a whole, these villages ended up less with low-yielding massal selections of Pinot Fin, more with high-yielding clones. In turn, with higher yields, grapes struggled to reach full phenolic maturity. Furthermore, the vineyards were (and still are) frequently machine-harvested and the grapes somewhat manhandled in the winery.

Certainly, one can argue that an appellation such as Saint-Aubin, with its cool, steep vineyards with little clay, is a tricky terroir, and that it requires the formidable talents of an Olivier Lamy to wrench from it a beauty unexpected. But with appellations such as Fixin and Santenay, it is less a case of the terroirs being complicated than of their having been caught in an economic vicious circle that created rusticity.

In fact, even though the soil in Fixin tends to be deep and clay-rich which normally results in powerful wines, three combes have provided an important alluvial component everywhere except on the upper slope. Consequently, Fixin’s clay is mixed with notable amounts of sand and silt which promote softness and elegance. Except for Les Arvelets, which is on the upper slope, elegance, airiness, lightness —the antithesis of rustic— are recurrent in our tasting notes for Amélie’s Fixins. It would appear that with the right vineyard work, and with precision in the winery, Fixin is not rustic at all.

Fixin Trivia

Fixin is not pronounced as in “I’m fixin’ to.” It is approximately pronounced “fi-san.”

What is now one village used to be two villages. Fixin and its immediate neighbor to the north, the village of Fixey, were united on January 28th, 1860.

Fixin is one of Côte d’Or’s smallest finage with only 124 ha planted to vines in village and premier cru (103 and 21 hectares respectively).

Fixin has eight premiers crus: Arvelets, Hervelets, Clos du Chapître, Clos de la Perrière, Clos Napoléon (Aux Cheusots on most maps), Les Meix-Bas, En Suchot, and Queue de Hareng (which is located in the village of Brochon.)

In practice, however, only five premiers crus are seen. This is because En Suchot and Queue de Hareng, which are adjacent to Clos de la Perrière, are allowed to be called by that name, and are blended into it by the Joliet family who own the entirety of the three vineyards; and because Les Meix-Bas is allowed to be called Les Hervelets, and what is left of it (most of it has been built on) invariably avails itself of the opportunity.

As we have hinted at, Clos de la Perrière is a monopole vineyard. Clos du Chapître and Clos Napoléon are also monopoles.

Apart from Clos Napoléon, the vineyard, you will find: Clos Napoléon, the restaurant; the Caveau Napoléon, Berthaut-Gerbet’s tasting room; Napoléon Awakening to Immortality, a statue by François Rude, a Dijon-born sculptor of national prominence; the Noisot museum, a replica of Napoléon’s residence while in captivity on Elba Island.

Fixin’s infatuation with Napoléon Bonaparte began in 1835 with Captain Claude Noisot. After having served in Napoléon’s army, including as a member of the Emperor’s guard during his exile on Elba Island, Noisot retired to Fixin. He purchased five hectares of land in the hills above the village and transformed them into a park where he planted Corsican Laricio pine trees. (Napoléon was from Corsica.) He had one hundred steps carved into the limestone bedrock to commemorate the Hundred Days, the period between Napoléon’s return from exile and the restauration of the monarchy. Noisoit then built the Noisot museum and commissioned the statue by Rude. He died in 1861. He had wished to be buried standing up, holding his sabre, and facing Napoleon’s statue so he could look upon it for eternity. Unfortunately, the bedrock proved too hard to dig. He was interred lying down where the ground was softer. Napoléon Bonaparte never himself visited Fixin. In 1850, his grandson Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, future President and Emperor, did visit Rude’s statue. He is rumored not to have liked it. We don’t disagree. It is a very depressing statue. Napoleon does not look ‘Awakening’ but very dead. His closed, R.I.P eyes leave few doubts about it. His bent knee pushes his blanket up, but because of its position, you can’t help thinking that it looks more like, um, a prominent case of rigor mortis. There is also a large dead eagle.

The Fixins of Domaine Berthaut-Gerbet

Fixin Village

Amélie’s Fixin Village is a blend of 4 separate lieux-dits in Fixin with a 40-year average vine age.

Fixey: 0.87 hectares (2.15 acres.) There are four lieux-dits with this name on the Fixin map. The Berthaut’s parcel lies just east of the village of Fixey.

Le Village: 0.5 hectares (1.24 acres.) There are several parcels with the same name on the map. The Berthauts’ parcel lies just south of Entre Deux Velles, towards the east. For those of you who have visited the domaine, it is the clos you see as you enter the courtyard of the caveau.

Le Pré: 0.5 hectares (1.24 acres.) It is nestled in the village of Fixin with houses surrounding it. For those of you who have visited, it is the vineyard you pass as you walk from the tasting room to the cellar.

La Sorgentière and La Vionne: 0.6 hectares (1.48 acres) and 0.1 hectares (0.25 acres) respectively, forming one parcel.

Soil and Bedrock

The first three parcels are similar: The soil is deep, 50 to 100 cm. It is rich in heavy clay, but with a notable amount of silt and sand, and it is only weakly to moderately calcareous. The bedrock is mostly sandy marl, except in the upper part of the Fixey lieu-dit, where it is Crinoidal limestone.

La Sorgentière/La Vionne is different: Soil is shallower, 20 to 50cm. It is clay-rich silty sand and weakly calcareous. The bedrock is white oolite and salmon conglomerate.

The Wine:

Though deep clay soils tend produce generously fruit-driven wines, the elegance from the sand and silt take over. Amélie underlines this in her winemaking: very little whole cluster, soft infusion, and a short, one year élevage in older barrels followed by a two-month resting period in foudres before bottling. Her village Fixin is a bright, delicious, and delicately-fruity wine. Structure is vintage dependent, but in general, it is not prominent, just a trace of linearity to anchor the fruit. It is also one of the great values for a village wine from the Côte de Nuits.

Fixin Les Clos

In 1896, Danguy and Aubertin mention M. Paul Berthaud and M. Pierre Berthaud as two of the three main proprietors in Les Clos. They also mention other Berthauts (with a ‘t’) as owners in the neighboring Champ Perdrix and Le Rosier; Domaine Berthaut-Gerbet still owns slivers of those. It would appear that these holdings have been in the family at least since the late 19th century.

Lavalle considered this area of Fixey to be very good. He included Les Clos, Le Clos, Le Rosier, Champs Perdrix, and Champennebaut in his deuxièmes cuvées, or second growths.

Location:

You will sometimes find Les Clos listed on maps as Les Clos Champs. It is not to be mistaken for ‘Le’ Clos, just east and downslope.

Situated in the north of the appellation, Les Clos is a 1.5 hectare (2.47 acres) vineyard, that lies mid-slope at approximately 310 meters’ elevation. The slope is gentle and faces slightly south of east.

Soil:

The geologic complexity found in the bedrocks of the site extends to the soils.

In general, the Combe Laveau has provided a notable alluvial input.

Throughout the vineyard, the soils are reddish-brown in color, with a rocky mixture of rounded alluvial cobbles from the combe, and more angular pieces of limestone, particularly the fossiliferous ostrea acuminata —you will find an abundance of it as soon as you step in Les Clos.

The northern portion of the vineyard is located out of the way of the combe, and there is a small section of shallow (<40 cm), highly calcareous, clayey, silty, sandy soils, with a notable colluvial component.

The alluvial soils to the south are variable in thickness (30-70 cm), weakly to moderately calcareous, and are often lighter in texture (silt, clay, sand) with abundant rounded limestone gravels and cobbles.

Bedrock:

Geologically, this area is extremely complex. Geologist Francoise Vannier has identified six faults just within this one vineyard. These faults have rearranged the underlying bedrock, and as a result, Amelie’s large parcel contains at least four different types of bedrock.

The upper, northernmost portion of the parcel lies on a mixture of the marly ostrea acuminata, and the harder, pink Prémeaux limestone. Farther to the south the vines sit on the fossiliferous Crinoidal limestone, or on the rounded alluvial material in the direct path of the Combe Laveau.

Berthaut-Gerbet Parcel:

With 1.3 hectares, the Berthauts own almost the entire vineyard. Their vines here range from 10 to 90 years old.

The Wine:

In the line-up of Amélie’s lieux-dits in Fixin, Les Clos is the odd one out, the lightest and airiest in texture, almost as if it were from a different appellation —it would be a tough blind.

‘Light’ used to be a four letter word for wine, but tastes are changing. Yesterday, we wanted dark, deep, extracted wines. Today, we increasingly crave vins de soif, quaffers. And so, Les Clos is not puny light, but beautifully light: aerial, thirst-quenching, and pretty, with vibrant acidity giving it a more of a red than a black feel, and with tannins that remain in the distant background, and that are softly chalk-like rather than gritty in texture. As with the Fixin village, its delicacy must certainly stem from the sand, silt and alluvial input.

It’s a Fixin for warm or hot weather, for spring and summer, for apéritifs, for charcuterie, for fish, for dishes with light sauces or no sauce at all. If you eat a lot of those things, in that sort of weather, then you should ignore the kneejerk reaction you may have to the word ‘light.’ Les Clos’ calling is not to compete —God bless it!— but to enhance.

Fixin Les Crais

Etymology:

“Crais” and its variant “Cras” do not appear to have any relation to the word craie, chalk, nor to the local patois for crow. Instead, it possibly stems from the Gallic word caracos, which meant stony hill or mass of fallen stones. (Source: Marie-Andrée Landrieu-Lussigny.) Given that the vineyard lies on alluvial sediments, namely stones rather than bedrock, this explanation makes sense.

Location:

Les Crais is 1.73 hectares (4.27 acres). It lies just east of the village, on the lower, very gentle part of the slope, at 280 meters’ altitude. It faces east-southeast.

Soil:

The soil is medium-deep, approximately 70 cm. It is brown, light, with a well-draining mixture of silt, sand, clay, and it is very rocky, with up to 40% rounded alluvial gravel and cobbles, and even the occasional large (10-25 cm), rounded boulder. Amélie notes that Les Crais is the easiest of her Fixin vineyards to work, which underlines how well-draining the soil is.

Bedrock:

Most of the vineyard is on thick alluvial sediments, primarily derived from the Combe de Brochon to the south, and the Combe Laveau to the north. In the upper portion of the vineyard there is salmon-pink limestone conglomerate.

The Berthaut-Gerbet parcel:

With 1.38 ha (3.41 acres) the Berthauts own most of the vineyard except for a bit at the bottom of the slope. Plantation dates range from 1946 to 2003, with an average vine age of 40 years old. The vines are planted N/S, across the slope.

The Wine:

In 1855, Lavalle ranked les Crais a second growth.

No matter the vintage, Les Crais always has a ripe, black fruit aromatic signature. This is logical since it is Amelie’s earliest ripening Fixin, and the one to achieve the highest maturity. But the nose also has lift from wonderful floral aromas. On the palate, Les Crais is Amelie’s broadest Fixin —the most Fixin of her Fixins. She hates the characterization, because she hears in it an accusation of rusticity, which is precisely the reputation she is doing such an amazing job at fighting. Les Crais is not rustic. But its lush and rewarding mouthfeel, and structure, is very much what you expect from the northern Cote de Nuits. The underlying acidity is remarkable, though: a total surprise because of the aromatic ripeness, and a welcome refreshment. On to the tannic structure: in 2016 it is quite fascinating, a two-step dance. First, in the mid-palate, where there is balanced, classic, tannic grip. But then, the finish is all beautiful, chalky tannins.

Les Crais is the polar opposite of Les Clos. It is a wine for fall and winter, for fireplaces. A classic wine for traditional pairings, for example for game in a red wine reduction, and if you don’t eat meat, for the best of all Burgundian dishes: oeufs en meurette (leave the bacon out).

Fixin En Combe Roy

Amélie’s father used to blend En Combe Roy in his Fixin village. But because of its special situation and because it has the Berthaut’s finest massal selections, she decided to vinify, age, and bottle it separately. In effect, she gave birth to it and she calls it ‘mon bébé‘, her baby. She is very attached to it. So are we.

Etymology:

According to Marie-Hélène Landrieu-Lussigny, Combe Roy is a deformation of Comberat, an ancient derivative of combe that meant rocky valley. Books from the 19th century state that Roy was the name of an ancient owner of the vineyard.

Location (and an utterly geeky discrepancy):

En Combe Roy’s total surface is 0.73 ha (1.8 acres.) Amélie owns 0.38 ha (0.94 acres) in the center of the vineyard with the domaine’s best massal selections, planted in the early 1960s.

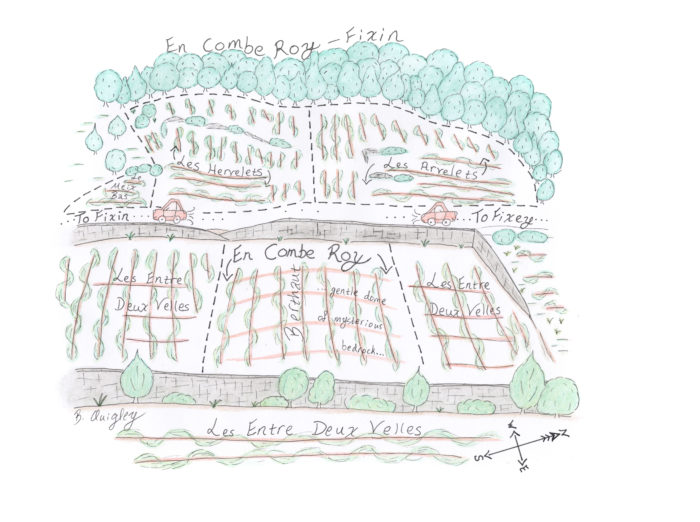

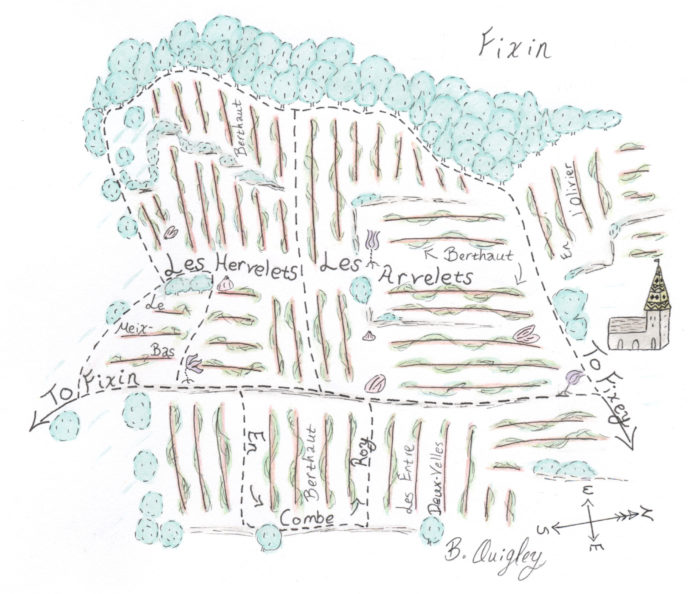

En Combe Roy faces east-southeast. Its slope is gentle. It sits at 300 to 310 meters’ altitude, just downslope from where Les Arvelets and Les Hervelets meet. It’s not a smooth continuation of the slope, however. A road separates En Combe Roy from the premier crus, and, as is often the case, the road follows a fault line. This one is particularly obvious: there is a two to three-meter depression from the road to En Combe Roy.

As to the vineyard’s other borders, interestingly, En Combe Roy is an enclave within the vineyard of Entre-Deux-Velles.

Entre-Deux-Velles is split mid-slope in approximate halves by a wall. The upper and lower parts have different geology and soils. En Combe Roy is in the center of the upper part and sits on a gentle dome. This physical aspect translates into a very obvious qualitative difference. We believe this is the reason that locals kept it as a separate lieu-dit.

Which ties into an interesting story.

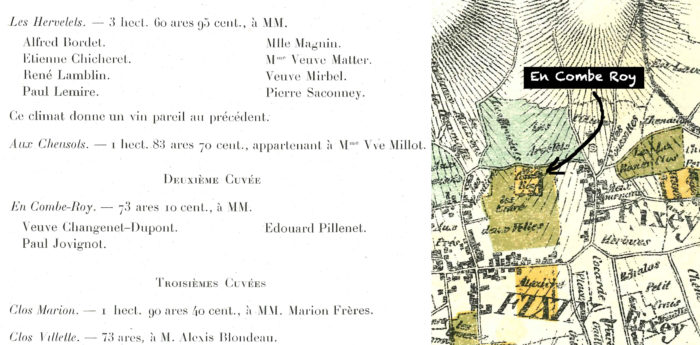

In two documents, one from 1871 and one from 1920, En Combe Roy is ranked a second growth, whereas the rest of Entre-Deux-Velles is ranked a third growth. However, in other editions of the same documents, En Combe Roy is ranked a third growth, whereas only the part of Entre-Deux-Velles directly south of it is ranked a second growth.

We looked into this in detail. However, we’re not going to share everything we found, for two reasons: First, we would have to go into minutia on the cartography of the vineyards Burgundy so tedious it would only be of interest to historians, archivists and bibliophiles. Second, when we were trying to piece together the reasons for these discrepancies, we believe we stumbled on some monkey business. Because it is mere speculation and such a minor and utterly too geeky footnote in history, we will let sleeping dogs lie.

To summarize:

There is a second growth in this area, in today’s terms, a super lieu-dit, and given what we have tasted from Amélie, one that could be argued to be a premier cru. It is either En Combe Roy, or it is the bit of Entre-Deux-Velles directly south of En Combe Roy. Different editions of the same documents contradict each other.

Even though more of the documentation points to a small part of Entre-Deux-Velles as the rightful second growth, it makes no sense. Why then is En Combe Roy the named, delimitated enclave? Why does it sit on a dome, whereas the purported second growth bit of Entre-Deux-Velles lies in a hole, never the superior situation?

We will leave you with documentation that bolsters the argument that Amélie’s baby, En Combe Roy, is the chosen one: the 1920 and first edition of Camille Rodier’s Le Vin de Bourgogne, where he names En Combe Roy as the single second growth in Fixin (he has three more in Fixey).

Soil:

Because of its lower position on the slope, and because of the lower wall which collects soil and slopewash, the soil in En Combe Roy is much deeper (>1 m) than in Les Arvelets.

It is weakly calcareous soil, with a mixture of clay, silt, and sand. It is lighter and has a more textural, gritty feel to it than in Les Arvelets. It contains significantly more gravel-sized rocks, but larger cobbles are less common, and only make up approximately 10% of the soil surface. The larger soil grains (silt, sand, and gravel) help drainage in the top layers, yet the soil tends to retain water at depth.

Bedrock:

When trenches were dug in Fixin for Françoise Vannier’s geologic studies, they were dug for Entre-Deux-Velles in the upper and lower parts of the vineyard, but not specifically in En Combe Roy. Because Amélie believes there could be a geologic explanation for her vineyard’s awesomeness, she plans to have a trench dug in En Combe Roy.

For now, we must go with the analysis of the trench dug in the upper part of Entre-Deux-Velles. The bedrock there is similar to what is found in the lower part of les Arvelets and les Hervelets: coarse-grained, sandy marl, with, in addition, several gravel banks.

The Wine:

In the hierarchy of Amelie’s Fixins, En Combe Roy definitely fits right between Les Arvelets and her other lieux-dits. But the more vintages under Amélie’s belt, the closer it nuzzles up to the premier cru.

In comparison to Les Arvelets, En Combe Roy it is more of a fruit-driven wine, less of a mineral-driven wine. Its fruit is generous and you would almost expect it to be followed by prominent structure in the mid-palate and the finish. Instead, it is elegant. The sandy nature of the soil and the gravel have an important influence here, as sand is a great promoter of elegance, and gravel of softness. The water retentiveness of the deeper soils also plays a role in relaxing the wine’s tannic structure. And we should also praise the winemaker: her extraction is increasingly delicate and precise.

The aromas are reserved yet profound and complex. They always have a red fruit, exotic spice, savory quality. And even in 2016, where the fruit is generally of the blacker type, the brightness is there, taking the aromas from the ripe flesh of black cherries to their pits, what the French admiringly call noyaux in their tasting notes.

In 2013 and 2014, we viewed En Combe Roy as Amélie’s fullest Fixin. The 2015 vintage was an anomaly because she declassified the older vines into her Fixin village. (They had been picked before the rain, and produced a wine that to her taste was overly structured.) In 2016, there is a class in the wine’s texture that renders the word ‘full’ inadequate: sounding a little more masculine, a little more brutish than the wine actually is.

Indeed, En Combe Roy’s most precious quality is texture. The wine’s textural reward is so beautiful and specific we are not sure we know of it in any other wine we represent. This is because from birth, its tannins are integrated, melded into the fruit as if they were fully intent on mastering a supporting role. The closest we can come to defining this texture is ‘nourishing’ —in a sensual yet maternal manner, like those dishes that on the first bite make you go “Ooo!” and stare at the heavens.

En Combe Roy is a special lieu-dit, a total heartthrob, and a giver.

Fixin 1er Cru les Arvelets

Etymology:

Arva is latin for cultivated fields; –let(s) is French for small, young, etc. Arvelets would therefore mean small cultivated fields. (Sources: Charlotte Fromont, Marie-Hélène Landrieu-Lussigny). Older sources state that the origin of the name is Arbelaie, Latin for a place where maple trees grow.

Location:

Les Arvelets is 3.36 ha (8.3 acres). It is the northernmost premier cru in the Côte d’Or. It lies between 310 m and 340 m altitude. The slope, overall, is moderate, which accuented by the fact that several large terraces have been created to fight erosion. It faces east, occasionally slightly southeast because of minor waves in the topography.

Soil:

The upper third of the vineyard has shallow soils (<40 cm) with a significant colluvial input from the limestone rocks found atop the hill. These soils are highly calcareous, and consist of a mixture of clay, silt and sand. They are light and textured. The lower two-thirds of the vineyard are on thicker (>50 cm) brownish-red, weakly calcareous, clayey soils. As a whole, the vineyard is rocky, with 15-30% gravel-sized or larger stones on the surface. Many of these rocks contain an abundance of fossils, and it is not uncommon to spot large, fully intact shells within minutes of stepping into the vineyard.

Bedrock:

Four different types of Jurassic limestone have been identified as the bedrock below the vineyard. At the bottom of the slope there are coarse-grained, sandy marls. The central portion of Les Arvelets is planted upon Crinoidal limestone. Just above this, faulting has exposed a sliver of fine-grained, pink Premeaux limestone. At the top of the slope, there is fossil-rich, marly ostrea acuminata.

The Berthaut-Gerbet parcel:

It is 0.96 hectares (2.37 acres) and it is located at the north end of Les Arvelets in the central portion of the vineyard’s slope on both sides of a small path that cuts through the vineyard. It is on the Crinoidal limestone and the sandy marls. The soil is the deeper, clayey yet stony type described above for the lower two-thirds of Arvelets. Amélie’s vines are planted across the slope instead of downslope. The average age of the vines is 40 years old.

The Wine:

In the inevitable comparison of Fixin with Gevrey, Arvelets reminded Dr. Lavalle of Clos Saint-Jacques. Clive Coates tut-tutted the comparison and we are sure that the kind of collectors who tend not to stray very far under the bar set by Clos-Saint-Jacques would also disparage the comparison. But Lavalle is the father of the vineyard classification of the Côte d’Or. He was the first to put it down on paper, thoroughly, with few errors, and in a manner that has stood the test of time. The man was no idiot.

But should one take Lavalle’s comparison seriously?

Clos-Saint-Jacques is at the top of the premier cru hierarchy, so much so that many think it should be a grand cru. It is a very complete wine, with something for everyone. The fruit on the front palate is gorgeous, fresh, more red than black, because it sits in the path of the cool air from the Combe de Lavaux. But what is most remarkable about the vineyard is its underlying mineral core. In that regard, Clos Saint Jacques is epic, one of the greatest and most satisfying expressions of stone in all of Côte d’Or —it combines force and class in the manner of an Olympian gold medalist.

It is difficult at this stage to pinpoint the personality of Amélie’s Les Arvelets. With young winemakers this serious and committed, every vintage is better than the previous regardless of the quality of the vintage because so many changes are in motion: vineyard work, winemaking, investments in equipment and in the physical workspace, not to mention the winemaker’s growing intimacy with her terroirs, which can change her opinion on the ideal picking dates for each vineyard, for example.

With the 2014 vintage, we would have said that Amélie’s Les Arvelets was reminiscent of Clos Saint Jacques in its red fruit character and its minerality. But in 2016, it is its depth and power that warrants the comparison, except that it is less of a red power, more of a black one, more Clos de Bèze, less Saint Jacques. Then again, that is a characteristic of the vintage.

Wherever Les Arvelets ends up stylistically, it is emerging as a truly great wine in the Berthaut-Gerbet cellar. For now, let’s just say that Clos Saint Jacques and Arvelets have a core that is particularly willful, as if it came from a deeper place, as if their calling was to brood on the serious things in life and carry the world on their shoulders; whereas the beauty of, say, Lavaux Saint Jacques (since Amélie makes that as well) is more alpine, adventurous, ethereal, and carefree. A tasting note for Clos Saint Jacques and Les Arvelets could include “May the force be with you.” A tasting note for Lavaux could include a picture of the Lady of the Snows —the flower, not the Saint. See Pulsatilla Vernalis.

Les Arvelets vs. Les Hervelets:

Originally there was only one vineyard: Les Arvelets. It straddled the villages of Fixey and Fixin. We assume it was when the villages were united in 1860 that the spelling differentiation was created. In an even more obscure administrative twist, Arvelets may be called Hervelets, but Hervelets cannot be called Arvelets.

But even though they have been separated by spelling, everyone says that Les Arvelets and Les Hervelets are really one climat. Geologist Françoise Vannier points out no major differences between the two in the geology and soil maps she recently completed for Fixin.

Why belabor the point? Because Amelie has baby vines in Les Arvelets and in Les Hervelets, planted at a similar elevation. Les Hervelets will be vinified separately but it will be blended at bottling in the Fixin village until the vines are old enough to express something compelling. But in the cellar at least, we will soon be able to compare Les Hervelets and Les Arvelets.