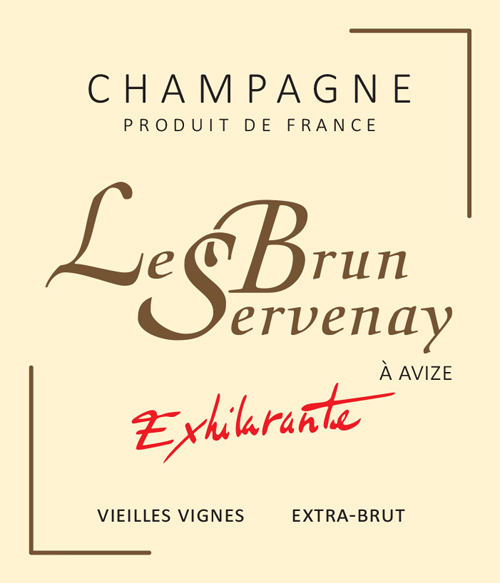

Domaine Profile

- Location: Avize, Côte de Blancs, Champagne

- Size: 7.00 ha (17.30 ac)

- Varieties: Chardonnay (80%), Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier

- Viticulture: Sustainable

- Vinification: Vinification and aging in stainless steel, malolactic fermentation blocked with thermoregulation and SO2, aging on lattes, hand-riddling, dosage with MCR or traditional liqueur.

“Only in wine does the ungrateful chalk pour out its golden tears.” —Colette

The bedrock of northern Champagne is chalk, a form of limestone. It is at its most ungrateful, with the least clay topsoil, in the Côte des Blancs. With little to no clay, this is where champagne tastes the most consistently chalky, cutting, racy, and suspenseful. To a certain kind of wine lover, Champagne is not champagne, the Côte des Blancs is champagne.

There is a new wave of ultra-talented growers in Champagne today. They favor riper harvests, wood, and oxidative techniques. Their wines can be stunning, but they are different. In some respects, the new winemaking is more minimal, but in others it adds elements that soften chalk’s ungrateful edge. A certain kind of wine lover sometimes feels nostalgic.

This is why Patrick Le Brun’s champagnes are precious. His holdings are superb, especially his extremely old vines in Avize and Cramant, two of the most assertively chalky terroirs in the Côte des Blancs. That is all that matters to him. He is a thoughtful man; he is aware of the current fashion. But he has chosen, as if were his duty, to be the guardian of a classic, non-malo, non-wooded, non-oxidative, Côte des Blancs esthetic. At this, he is one of the best.

History

On Patrick’s father’s side, the Le Bruns tended vines in Avize for four generations. On Patrick’s mother’s side, the Servenays tended vines in Mancy, just a few kilometers west of Avize, for five generations. Things were difficult in Champagne during the two world wars; his grandparents could not make a living only from their vineyards. Grandpa Le Brun worked other people’s vines while the Servenays owned a small grocery store.

It was a little easier for the Le Bruns, though. There is always a buyer to be found when your vineyards are in Avize and Cramant. The Servenays, on the other hand, were forced into estate-bottling. “At the time, the négociants bought when the harvest was abundant and prices were low,” says Patrick. “When they didn’t buy, barrels of wine remained unsold in the cellar. But those barrels were needed to house the following harvest. So my grandparents had no choice but to estate-bottle some of their champagne.”

The champagnes then needed to be sold. “My grandfather had family in the Vosges, in Remiremont. He would hitch a small trailer to his motorbike, pile fifty bottles in it, and drive the 175 miles from Mancy to Remiremont. Can you imagine? With the bike and the roads of the times?” It paid off. The Servenays’ private clientele grew steadily by word of mouth.

In 1955, after Patrick parents married, they created the Le Brun Servenay label. They were the first generation in Patrick’s family to make a living solely from their vineyards. And with their growing private clientele, “until the 1990s, we barely exported,” says Patrick, “we didn’t need to.”

Patrick Le Brun

Though Patrick was born on November 1st, 1962, there were grapes in the press. It is one of the latest harvests on record.

In 1983, he attended the viticulture and oenology school in Mâcon. To his parents’ despair, he came home after just one year. Patrick worked happily alongside his father. In conversation, he always shows great respect for the man as well as the wines he made. The domaine was then comprised of 4 ½ hectares. Patrick added a few more, some rented, some purchased, some as far as the Sézannais.

In 1991, Patrick was suddenly left to make the vintage on his own after his father fell off a tank and ended up in the hospital, missing harvest for the first time since he was 15 years old. In 1992, Patrick fully took over his family’s domaine. In 2002, he added 4 more hectares, some in Mancy, some in the Vallée de la Marne. After he divorced, the domaine was pruned back to the 7 ½ hectares it is today.

Patrick looks straight into your eyes, tells good stories, and laughs regularly and self-deprecatingly. He is as genuine as he is frank —to the point of getting into trouble.

In 2008, the French government awarded him the title of Chevalier de l’Ordre du Mérite Agricole (Knight of the Order of Agricultural Merit) for his work as president of the SGV, the Champagne Growers’ Union. He held the position from 2004 until 2009, and was elected to the presidency twice. Then, only five months after his reelection, he was booted by the union’s board. Officially it was for being “despotic.” Unofficially it was for refusing to drop charges of theft and embezzlement involving someone else in the union, as well as for brokering a controversial contract with the big champagne houses.

Because the latter is an interesting insight into how the region works, here is what happened:

In Champagne, small growers own roughly 90% of the vineyards, but the big houses commercialize about 60% of the region’s production. This has led both parties to privilege collective bargaining over speculation, with mid to long-term grape contracts. Maximum yields for all of Champagne and grape prices are thus set every year after negotiations between small growers and big houses.

In 2009, Champagne was hit hard by the recession; sales dropped by 30%. The upcoming vintage promised unusually abundant yields, as it did in the rest of France. Faced with economic adversity but grape contracts to honor, the big houses wanted a 50% reduction in maximum authorized yields.

As president of the growers’ union, it fell upon Patrick to negotiate. He convinced the big houses to agree to a 30% reduction in yield in exchange for lower grape prices and slightly deferred payments.

His opponents at the union claimed that he had been too amenable to the interests of the big houses. But the British agent for a big house was quoted in the 2010 Champagne Report: “I have spoken to many people in the industry on both sides of the fence, I am yet to find anyone who is satisfied with the result, which has rather led me to believe that a reasonable compromise was perhaps found.”

An Elephant in the Room

Normally, one doesn’t discuss a domaine one represents by comparing it to a domaine one does not represent. That would be acknowledging the existence of other intelligent life and wine importers don’t do that. But there is an elephant in Avize too large to ignore.

In 1974, when Anselme Selosse returned to the family domaine after his studies in Beaune, he brought to Champagne a Burgundian winemaking philosophy. He picked his grapes later than the norm, and he vinified his parcels separately in oak barrels. It was only the beginning of whole set of revolutionary winemaking practices. Anselme’s wines quickly rose to deserved cult status, and he inspired a whole generation to follow his example. He is the godfather of new wave champagne.

Though it would be futile to attempt to pigeonhole the new wave, it is a family. There is a particular and compelling taste to these champagnes. Whereas classic champagnes develop umami after extended cellaring, new wave champagnes have it at birth. There is no denying the role of improved viticulture in this youthful umami, but to paraphrase Glenn Gould, there is a lot of winemaking going on here.

Lower dosage plays a role as it lets more saltiness through. Other methods have a fattening, and/or reductive, and/or oxidative effect: lower or no additions of sulfur, a laissez-faire attitude towards malolactic fermentation, aging on the lees (with or without bâtonnage), in wood (small, large; old, new), sometimes with flor, the addition of soleras in blends as a replacement for reserve wines (or the soleras bottled on their own), aging with cork rather than crown caps, etc.

Take all of the new wave methods, leave them behind except for lower dosage and aging on the lees, now go to the other side of the room: Le Brun Servenay.

Very Old Vines, Winemaking, Etc.

Le Brun Servenay owns 7.5 hectares. There are 3.5 hectares in the Côte des Blancs communes of Avize, Cramant and Oger. One hectare is located in the premier cru commune of Grauves (where Richard Juhlin’s single favorite champagne, Pol Roger’s 1928 Grauves, comes from). And the balance, 3 hectares, are located in Mancy.

The domaine’s style must first be credited to a high percentage of old vines. The average is 35 years old on the non-vintage wines, and 65 years old on the vintage wines and the rosé.

There is no wood: all his wines are vinified in stainless steel tanks but for one, the red Coteaux Champenois, which is aged in two older barrels, and blended in the rosé.

There is no malolactic fermentation (except for the coteaux again): Almost never. Patrick’s tanks are thermo-regulated. His cellar and equipment are nearly free of lactic acid bacteria. He does use sulfur to help block the malos, but because he wants to use it in moderation, on rare occasions a tank may undergo a very partial malo (single-digit percentiles).

He does age his reserve wines on fine lees, and there can be up to four vintages used in his non-vintage cuvées. No soleras though.

Patrick makes the still wines in his winery in Mancy. But the prise de mousse, aging sur lattes, and riddling are done in the underground cellars of his family’s house in Avize. The cellars are small and there is no room for gyropalettes. So riddling is mostly done by hand, sometimes with one of those old mechanical riddling-machines, so antiquated it looks comical.

Dosage is a perpetual question for Patrick, “almost existential”, he says. For a while he swore by MCR. But his father could tell the difference in blind tastings; he had a clear preference for traditional liqueur. For the moment, the matter remains unresolved. Some wines are dosés with MCR, others with liqueur.

Patrick Le Brun’s champagnes, in their youth, do not have much of the new wave’s winemaking umami. You’ll have to cellar them for that; they age magnificently. But there is saltiness to be found simply from the old vines and chalk of the Côte des Blancs. And there is a great feeling of purity to them. On the lunar calendar days that do not emphasize structure, Patrick’s wines often feel incredibly free of the clutter of winemaking, like the archers to the rest of Champagne’s artillery. And on the days that do emphasize structure, his wines have that searing edge, that wonderful, near painful quality we once associated with the Côte de Blancs. They’re not old school though. Just a reminder of unadorned chalk.

Here is Colette’s entire paragraph; there is no mention of winemaking: “The vine and the wine it produces are two great mysteries. Alone in the vegetable kingdom, the vine makes the true savor of the earth intelligible to man. With what fidelity it makes the translation! It senses, then expresses, in its clusters of fruit the secrets of the soil. The flint, through the vine, tells us that it is living, fusible, a giver of nourishment. Only in wine does the ungrateful chalk pour out its golden tears.” (Prisons et Paradis, 1932.)