Welcome to Loire Volcanique

With many thanks to Jim Sligh for the maps. Copyright Children’s Atlas of Wine.

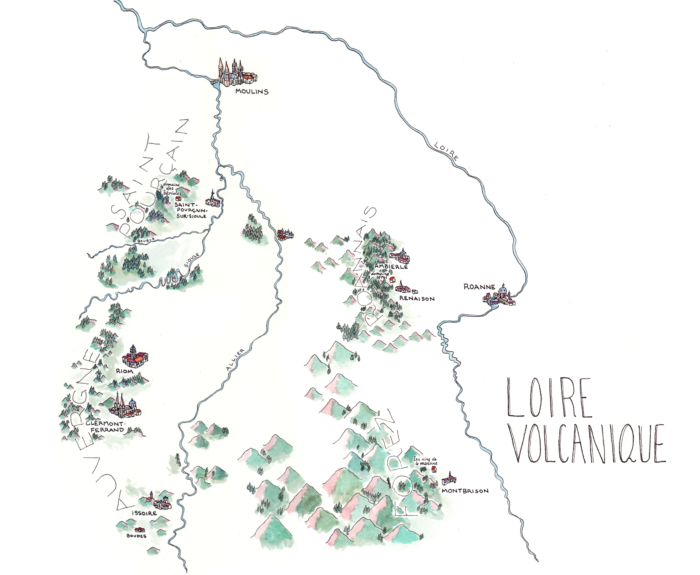

Even the official website for the wines of the Loire Valley has an incomplete vineyard map. Most of them are. They display the final 400 kilometers of the Loire, a tidyish, horizontal axis beginning in Sancerre and ending in Muscadet, where France’s mightiest river surrenders to the Atlantic. “See? Easy to understand,” the maps say. Which makes you want to sock them in their gerrymandering little faces because the Loire’s source is several hundred kilometers southeast of Sancerre, and somewhere down there, there are four more appellations: Côtes d’Auvergne, Côte du Forez, Côte Roannaise, and Saint-Pourçain.

Why leave them out? Because they are remote. Including them would reduce the map’s scale; mess with mapping feng shui. Who will notice their absence anyway?

On March 9, 2020, in the village of Ambierle, three dozen vignerons from the four remote appellations came together under the banner “Loire Volcanique.” They respectfully ask us to notice.

Ambierle. March 9, 2020.

Somewhere down there. Copyright Children’s Atlas of Wine.

LOIRE VOLCANIQUE: THE ESSENTIALS

Loire Volcanique is not an official appellation or sub-region but the name chosen by an association of 35 domaines plus one cooperative to brand the wines of Côtes d’Auvergne, Côte du Forez, Côte Roannaise, and Saint-Pourçain. The association is open to all domaines in the region and its membership will certainly grow.

We have the pleasure of working with Domaine Sérol in the Côte Roannaise, Domaine des Bérioles in Saint-Pourçain, and Les Vins de la Madone in the Côtes du Forez. All three are either certified biodynamic or completing the certification process.

Loire Volcanique is named because of location: The four AOPs, with a total of 1,350 ha planted to vines, are located on the foothills of the Massif Central, the largest of the French mountain ranges, home to most of the French volcanoes.

Loire Volcanique is also named for its geology, but not dogmatically: the Massif Central is mostly composed of igneous and metamorphic rocks, especially granite, however, there are alluvial sediments in Saint-Pourçain, and limestone in Saint-Pourçain and the Côtes d’Auvergne.

Loire Volcanique intelligently embraces all wines produced in the region, whether or not they adhere to the local AOP or IGP regulations. Vins de France are welcome under the Loire Volcanique banner.

If you want a soundbite for Loire Volcanique, it is Gamay on granite. Gamay is the most widely planted variety in the region and granite is the dominant rock. Furthermore, two of the four AOPs, Côtes du Forez and Côte Roannaise, are for Gamay only. But despite the similarity in geology and grape, Loire Volcanique is not lesser Beaujolais. The vineyards are located at a higher average altitude in Loire Volcanique. And though there is Gamay noir a jus blanc (Beaujolais’ Gamay), there are local biotypes: Gamay de Saint-Romain and Gamay d’Auvergne. These factors contribute to Gamays that taste edgier and more savory.

Tressallier, a biotype of Burgundy’s Sacy, is the treasure of Saint-Pourcain. It produces a crisp, salty, nervy white wine, texturally in the same glass pour zone as Aligoté, Melon de Bourgogne, and Sauvignon Blanc. Incidentally, in the Middle Ages, Saint-Pourcain produced some of the most expensive wines in France.

Pinot Noir and Chardonnay are usually planted on the limestone terroirs in Saint-Pourçain and Côtes d’Auvergne. Pinot Noir was most likely introduced into the region in the Middle Ages.

Poteé Auvergnate at the launch of Loire Volcanique

Carine and Stéphane Sérol

Biodiversity in Les Blondins, a vineyard co-owned by the Sérols and Michel Troisgros of Maison Troisgros

CÔTE ROANNAISE

AOP Côte Roannaise:

Reds and Rosés: 100% Gamay Noir, though typically with the region’s own biotype: Gamay de Saint Romain.

The village of Ambierle has the right to the additional designation Rosé d’Ambierle.

IGP Urfé:

Reds and Rosés: Gamay Noir, Syrah, Pinot Noir.

Whites: Chardonnay, Viognier, Roussanne, Pinot Gris, Aligoté, Chardonnay, Gewurztraminer.

Surface: 215 ha currently planted.

Terroir:

The Côte Roannaise is located on the foothills of the Monts de la Madeleine, on granitic ridges that run perpendicular to the mountain. The vineyards are on the south-facing slopes of the ridges, where they tend to be steep, and on the top of the ridges where they face east and are moderately steep. The vineyard area is only 25 km long and 1km wide but it is not continuous. The vines are scattered among other crops, pastures for the grazing Charolais cattle, and woods. This biodiversity is a great advantage over the monoculture we find in so many wine regions.

With vineyards planted between 400 meters and 550 meters, the Côte Roannaise is at a much higher average altitude than the Beaujolais, which is a determining factor in the differences in feel and taste of their gamays.

The Côte Roannaise and much of the Loire Volcanique benefit from cold, dry winters and warm, dry summers. This is due to the “Foehn effect”: precipitations traveling from the Atlantic Ocean to the West are in part stopped by the western slopes of the Massif Central; the air mass becomes warm and dry by the time it reaches the vineyards.

The terroir is pretty uniformly pink granite, with some variation at the top of the slopes: volcanic tuff to the south, microgranite in the center, granite in the north.

The Wines:

In a nutshell, Côte Roannaise is Gamay on granite. However, this does not make it another Beaujolais, let alone a lesser one. Its wines are not as dark-fruited —they are fresher, they have clearer nerve and cut, and they walk a thin line we adore, one that lies on the frontier between the realms of fruit and savory-vegetal. If Beaujolais is reminiscent of deliciously crunchy black or blue berry juice, Côte Roannaise is part blood orange and tapenade. There is a lovely French expression for people with an irresistible but unconventional charm: Ils ont du chien, they have dog. The Côte Roannaise has dog. The only reason it is not yet well-known is because of its small size and the existence of few great domaines to raise it in the consciousness of wine nerds. But with hundreds of hectares of affordable granitic vineyard land left to plant, it is attracting young winemakers.

Gamay de Saint-Romain:

There is Gamay Noir à Jus Blanc (Beaujolais’ Gamay) in the Roannais but the region remains committed to Gamay de Saint-Romain.

Gamay de Saint-Romain is a biotype of Gamay Noir à Jus Blanc. According to the vignerons in the Côte Roannaise, it is named after Saint-Romain-la-Motte, an important wine-growing village from the 17th to 19th centuries. According to the vignerons in the Côtes du Forez, it is named after the Pic de Saint-Romain-le-Puy, a small volcano on the outskirts of Montbrison.

Pierre Gallet (Encyclopédie des Cépages, 2005) states that it is a biotype of the Plant des Trois Ceps or Gamai de Saint-Galmier described by Count Odart in his Traité des Cépages (various editions, 1845-1874).

Odart: “PLANT DES TROIS CEPS ou GAMAI DE SAINT-GALMIER (canton de l’arrondissement de Montbrison). This is again a new Lyonnaise, which is what the Gamais are called in the Allier. It was found 36 to 40 years ago by a farmer in his field, and grown with care. It is named after three small vines that had come out of the earth, very close to one another. Neighbors who had noticed that the vines gave better fruit than their common Lyonnaise, propagated the vines. Later, M. de Meaux, a wealthy person from Montbrison, planted several hectares of it. He had reasons to be pleased because of the healthy yields and the great quality of the wine. It is from him that I have received this information. He added that the vignerons who grow this variety have no doubt as to its parentage with Gamai Noir or Lyonnaise. Since I started cultivating it, its yield has always been moderately high, its ripening easy, and its resistance to humid weather leaving nothing to envy. My last acquisition from this tribe is a variety known as GAMAI DE SAINT-ROMAIN. I can say little more about it than what I learned from the gracious proprietor from whom I received it, M. Chaverondier from Roanne. This is because the few grapes I had in 1863 were devoured by badgers. ‘This variety,’ he wrote to me when he sent me a few cuttings, ‘combines yield and fruit quality, so much so for the latter that the finesse and taste of the grapes has made several connoisseurs doubt the accuracy of its attribution to the family of Gamays.’”

History:

Historians suspect there was a great expansion of viticulture in the Roannais contemporaneously with that of the Macônnais, because in 938, the local Abbey of Ambierle joined the Order of Cluny.

In 1642, upon the completion of the Canal de Briare that linked the Loire and the Seine rivers, Roanne became the major hub for commerce between the south and the north of France. Vignerons close to Roanne took advantage of the city’s strategic position. It is estimated that at its height, the Roannais had 20,000 ha of vines, 5,000 of which were qualitative and planted on the Côte. The region’s most famous wines came from Renaison, home to Domaine Sérol, and were sold in Paris as Vins d’Arnaison.

An all too familiar litany contributed to the demise of the region. The development of the railway in the second half of the 19th century provided more convenient and economical means than waterways for wine to reach Paris. Then there was phylloxera, oidium, mildew, a succession of difficult vintages in the early 20th century, two world wars, the great frost of 1956… By the 1970s, the vineyards of the Roannais had dwindled to 200 ha, all of them on the Côte.

The AOC Côte Roannaise was granted in 1993, due in great part to the efforts of Robert Sérol and the support of Pierre Troigros of the famous local restaurant Les Frères Troigros.

Granite at Bérioles

Jean Teissèdre, Domaine des Bérioles, at the launch of Loire Volcanique

SAINT-POURÇAIN

AOP Saint-Pourçain:

Reds: Gamay (min. 40 to max. 75%); Pinot Noir (25 to 60%)

Whites: Chardonnay (60 to 80%); Tressallier (20 to 40%); Sauvignon Blanc is optional (up to 10%)

Rosés: Gamay (100%)

IGP Val de Loire:

Wines that do not fit within the constraints of the AOP may be labelled as IGP Val de Loire, a large IGP encompassing and numerous grape varieties and 14 départements (French states, sort of). Single variety wines are authorized, such as 100% Tressailler, though it is angering that they must be demoted to an IGP.

Surface: 600 ha currently planted.

Terroir:

With 600 ha planted to vines from a potential for 800 ha, Saint-Pourçain is the largest of the Loire Volcanique appellations. Yet, this is nothing compared to the 10,000 ha described in the early 19th century.

Vineyards are scattered among other crops at an altitude of 250 to 400 meters to the west of the Allier river, a major tributary of the Loire. Moving west from the Allier, the first terroir is on the river’s alluvial deposits of sand and gravel. The second terroir consists of a low ridge of clay and limestone. Just behind it, the shallow valley of the Sioule river takes advantage of a major fault that separates the limestone ridge from a third terroir, the granite and gneiss of the Massif Central foothills. In general, you will find Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Tressailier on limestone; Tressailier and Gamay on granite and gneiss.

The wines:

The grape varieties authorized in Saint-Pourçain have geological reasons to be there and most have been documented there since the early 18th century —Pinot, it could be argued, as far back as the Middle Ages. First appearing in writing in 1250, the name used for the Pinot family around Orléans was Auvernat, meaning from Auvergne, the local cultural region. This implies that Pinot came to Orléans from Auvergne at least as far back as the 13th century. (A thesis by Henri Galinier disputes this.)

Chardonnay, however, is a recent arrival. It was almost non-existent in Saint-Pourçain before the 1960s (Saint-Pourçain, Antoine Paillet and Pierre Citerne). Yet, when the AOC was created in 2009, it was named the ‘principal’ white variety. It must now comprise at least 60% of any white AOP Saint-Pourçain.

Tressallier, the AOP’s ‘secondary’ variety, is not only a more interesting wine, it is almost exclusive to the region. The etymology of Tressallier is a derivation of trans-allier, meaning from across the Allier river. Indeed, it came here from Chablis, where it is known as Sacy.

DNA testing at UC Davis has shown Sacy to be a cross of Gouais Blanc and Pinot, like 20 other varieties including Chardonnay, Aligoté, and Melon de Bourgogne. The feel and taste of Tressallier is much closer to the street smarts of Aligoté and Melon than it is to the luxe of Chardonnay. It produces a crisp, energetic, salty, and pungently tart white wine, texturally in the same glass pour zone as Aligoté, Melon de Bourgogne, and Sauvignon Blanc. But it can also be profound: Domaine des Bérioles’ Autochtone, a 100% Tressalllier grown on Granite and labelled as IGP Val de Loire for its lack of Chardonnay, points to the variety’s ability to feel deeply mineral.

Tradition says that Sacy was imported from Italy to France in the XIIIth century by the monks of the Abbey of Reigny, located 20 km south of Chablis, next to a stream called Ru de Sacy and 7km from the hamlet of Sacy.

Sacy and Tresallier are rare. Some can still be found around Chablis but only in Côteaux Bourguignons and Crémant de Bourgogne. There are only 30 to 80 ha planted in France, the bulk of them in Saint-Pourçain.

Incidentally, there would be several historically correct white varieties to explore here. A local conservatory includes Aligoté, Melon de Bourgogne, Meslier Saint-François, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Romorantin, and Saint-Pierre-Doré. In addition, in 1816, Jullien mentions Verdurant (Chenin Blanc).

History:

Saint-Pourçain was once one of France’s most prized wines. Roger Dion, France’s best wine historian, was a stickler for written records and never used hyperbole even if he was sometimes prone to bias. It was only because of abundant documentation that he attested to “the extraordinary favor bestowed during the Middle Ages, particularly during the XIIIth and XIVth centuries, on the wines of Saint-Pourçain.” Purchase records place Saint-Pourçain on the tables of the Kings of France, the Popes in Avignon, and the Dukes of Bourbon. But most surprising is a royal ordinance from 1360 separating wines into tiers for the purpose of collecting duties upon their arrival in Paris: “In the lower tier are the vins François [wine produced from Paris to the Marne], estimated at 13 pounds per queue [894 liter barrel]; in the middle tier, the wines of Burgundy [those from Auxerre and surrounding vineyards], the average price of which is estimated at 26 pounds per queue; lastly, the wines of great price, such as Beaune, Saint-Pourçain, and foreign wines [sweet wines imported from the Mediterranean].” The Saint-Pourçain wines in favor at the time were white, as well as oeil de perdrix, a highly-prized rosé or light red, the color of a partridge’s eye.

Gilles Bonnefoy, Les Vins de la Madonne, and his intern Solène

Looking at “The Shire” from the top of the Madone volcano

CÔTES DU FOREZ

AOP Côtes du Forez:

Reds and Rosés: 100% Gamay Noir, though typically with the region’s own biotype, Gamay de Saint Romain.

IGP Urfé:

Reds and Rosés: Gamay Noir, Syrah, Pinot Noir.

Whites: Chardonnay, Viognier, Roussanne, Pinot Gris, Aligoté, Chardonnay, Gewurztraminer.

Surface: 150 ha currently planted.

Terroir:

Côtes du Forez is the smallest and therefore the most obscure appellation in the Loire Volcanique. The vineyards are even more scattered than in the Roannais and Gilles Bonnefoy from Les Vins de la Madone is the only vigneron in the village of Champdieu.

Champdieu is Shire-like. The region is softly hilly. Gilles’ vineyards are small islands in the middle of pastures, forests, and other crops. Standing at the top of one of his vineyards, Gilles points to a few rows of vines planted on a very small hill. “It’s a volcano,” he explains. Really?! We cock our heads to measure it. Volcanoes normally conjure up visions of might and destruction but this one is so petite and cute we want to order one for our own garden. In the distance, another petite volcano, the Pic de Saint-Romain, is so perfectly cut out against the horizon it looks like it was taken from The Map of Middle Earth.

Yet, volcanic activity there was, and it has created a great diversity of geologies here. Besides granite, you will find basalt, migmatite, and dacite. And, according to Gilles, the most differentiating feature with the Roannais is an abundance of (granitic) clays —up to 30%.

The altitude is even a tad higher than in the Roannais with several vineyards reaching 600 meters.

The wines:

Côtes du Forez is the Côte Roannaise’s twin but not its identical twin. It too is mostly about Gamay de Saint-Romain, mostly on granite, at similar altitudes. But the presence of clay creates a different texture. Forez is the Roannais with a muffin-top. There is a little more cushion on the front-palate. The wines are a little darker too and with more spice. Yet they remain more savory and altitude-fresh than in the Beaujolais.

History:

A deed from the Abbey of Savigny in the Rhône first documents the presence of vineyards in 980 A.D. In 1883, there were 5,043 hectares of vineyards in the Forez. They were devastated by phylloxera, etc. The AOC was created on February 23, 2000.

Left to right: Dacite, Basalt, Migmatite

To the right, the volcano’s crater with its dark basalt rocks. To the left, volcanic activity has done violent things to the light-colored limestone on the volcano’s flank.

NOTE: We do not yet work in the Côtes d’Auvergne and will leave that presentation to presently more legit people than us.

#LOIREVOLCANIQUE

@loirevolcanique

www.loire-volcanique.com